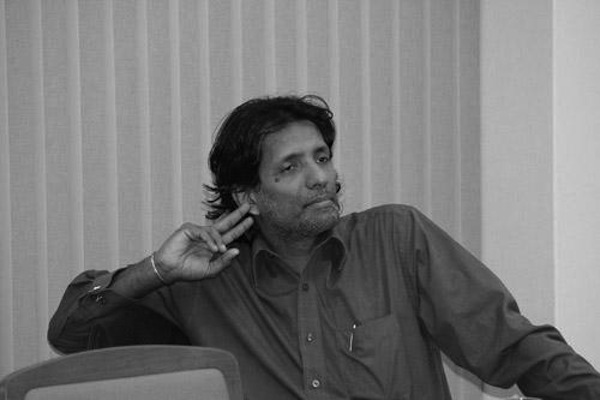

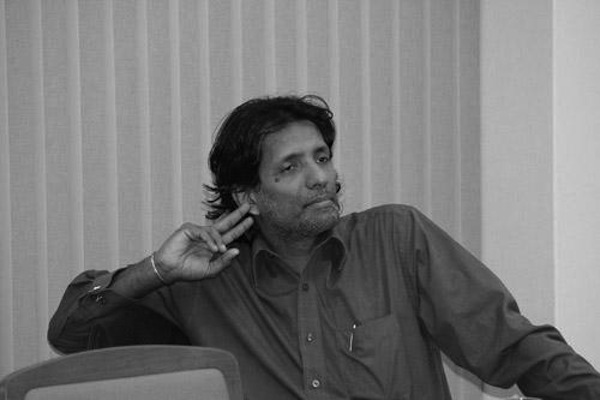

The following is an interview with Professor Sasanka

Perera of the South Asian University conducted by Mr. Ranjit Perera of

the Social Scientists Association of Sri Lanka via Skype on 18th August 2012.

The following is an interview with Professor Sasanka

Perera of the South Asian University conducted by Mr. Ranjit Perera of

the Social Scientists Association of Sri Lanka via Skype on 18th August 2012.

Ranjit Perera: Cyberspace and virtual reality are

intertwined in the context of today’s communication technology; this

came to my mind while conducting this interview. Any thoughts on that

before we get down to more serious issues?

Sasanka Perera: Well, I am hesitant to get into a

philosophical discussion on these matters in an interview meant for

popular consumption. I guess we can have this chat separately. But

briefly, yes. This interview would not have taken place across national

borders if not for the internet and the fact that technology within it

is accessible, cheap and democratic in its reach. But this is not

virtual; you are there asking questions. I am here trying to answer

them. The only issue is that the physical distance between us have been

bridged because of the availability of certain technologies, which in

this case is Skype. I can see that the internet and its technologies

have been widely used in the context of the ongoing strike and related

activities of the Federation of University Teachers’ Associations. Its

internet presence literally seems like that group has jumped almost

overnight from what appeared to be pre-modern ages right up to

postmodernity. That is one reason I can still keep up with what is going

on even from New Delhi despite the misinformation routinely

manufactured by state media and uncritical sympathizers of the regime.

Ranjit Perera: Let’s talk a little bit about your recent

association with New Delhi. That was last year wasn’t it, soon after

your fieldwork in Tokyo was completed?

Sasanka Perera: Yes. I undertook fieldwork in Tokyo while

teaching there on sabbatical leave from about late March 2011. I arrived

in Japan two weeks after the devastating East Japan Earthquake and

Tsunami hit the country. I was one of the very few foreigners who came

to the Hitotsubashi University where I was based at the time. My

intention was to undertake limited ethnographic fieldwork focused on the

Sinhala immigrants settled in Tokyo; some were very legitimate; but

many were literally living under the radar. The second part of the

research was supposed to be in New York in association with Cornel

University. For that, I had already won the Fulbright Fellowship. My

hope was to undertake the same kind of research in New York as it was a

more established diasporic centre for the Sinhalas. This was supposed to

be a comparative study to understand how home was recreated away from

home and how a sense of cultural identity and affiliation was

transformed or did not change in the context of migration and settlement

in a new country; in a new city. But the New York part of the research

could not be undertaken as I ended up in New Delhi, and as a result, I

declined my Fulbright Fellowship as well.

Ranjit Perera: How did this happen? Not too many people

would willingly give up a Fulbright scholarship, and would opt to go to

New Delhi instead of New York.

Sasanka Perera: May be you are right. But for me, New York

is not some kind of an emotional site where I was dying to go. It was

simply a research location just as much as Tokyo was, Katmandu was years

ago and many locations in Sri Lanka, from Anuradhapura to Kandy and

Kataragama. But from a research point of view, it was a pity I could not

go to New York to complete my work as planned. As it is now, I have the

material from Tokyo only. So either I have to write up my research

based on the work in Tokyo or schedule to visit New York again sometime

in the future to complete what was originally planned. But right now, it

is very difficult for me to plan something like that given my somewhat

hectic work schedule. From an ideological point of view, the diversion

to New Delhi was not a difficult thing to do.

Ranjit Perera: You mean your affiliation with the South Asian University? How exactly did this happen?

Sasanka Perera: Well, many years ago a group of friends from

across South Asia met at different locations in the region to discuss

the possibility of such a university. I came into the circuit quite

late. There were people like Imtiaz Ahamed from Bangladesh, Ashish Nady

from India, Kanak Dixit from Nepal and many others involved in these

discussions. It was grand plan to establish the university with

different faculties in different cities. It was grand, intensely

challenging and completely unpractical as I know now. So it fizzled out,

and the people involved went in different directions. But for me, it

remained an extremely interesting idea that was worth pursuing though in

a more pragmatic scale. Years after all this, the Prime Minister of

India, Dr. Man Mohan Singh came up with the same idea. But his was a

more pragmatic idea, to create a South Asian University accessible to

scholars and students from the region as a centre for producing cutting

edge knowledge and base it in one city while the possibility of

establishing regional centers in other cities exist in the present plan.

This was a very powerful idea that had the backing of the Government of

India and all other countries in South Asian Association of Regional

Cooperation. All these countries except Pakistan at present fund the

university; India spends an enormous amount of money on the construction

of a new campus in New Delhi which has not started yet. We have about

100 acres of land. India also spends considerable funds for scholarships

for students. Right now, the university is based in Akbar Bhawan,

Chanakyapuri which is the diplomatic area of New Delhi.

Ranjit Perera: So the university invited you to join its staff?

Sasanka Perera: No, there was a letter that was sent to many

universities in the region by the president of South Asian University. I

got a copy of it directed to me by the Vice Chancellor of the Colombo

University, and I simply sent in an application. As I said before, I was

already attracted to the idea in ideological and intellectual terms.

Besides, the challenge of actually setting up a brand new institution

for intellectual excellence for young people from our region was quite

enticing. So I was interviewed while I was in Tokyo, again by Skype.

Think about the world without this kind of cheap technology. It would be

a very different place. This was in June 2011 I think. About a month

after the interview, I was offered the job as Professor of Sociology at

the new department that was about to start, and it was agreed that I

could assume duties in late October or early November 2011 once my work

in Japan was over.

Ranjit Perera: So you are the founding professor of sociology at South Asian University?

Sasanka Perera: Yes, but it is more complicated than it

seems. Soon after I arrived numerous administrative responsibilities

fell on me that I hardly had the time to breathe. These are the kinds of

things that I very judiciously avoided in Colombo except for the last

two years or so when I ran out of excuses and choices. So less than one

year since I assumed duties, I am not only the founding chair of

sociology but also the founding Dean of the Faculty of Social Sciences.

Strangely enough, I am also the chair of the Department of International

Relations, a discipline I know only as a layman. This happened due to

the lack of senior scholars to take over these responsibilities. But I

think now the issues with the International Relations Department could

be handled effectively as we have recently recruited many young scholars

as well as two senior scholars who can lead the department. I think IR

will now begin to grow. One of the things I have insisted on over the

last 10 months or so and would continue to do so, is the need to

introduce inter-disciplinary courses and approaches within the

intersections of sociology and international relations as disciplines,

and beyond. This is one of the things I would like to see happening with

the induction of new people into both IR and Sociology Departments over

the next year or so. As it is, I think the Faculty of Social Sciences

and the two departments currently located in it are doing quite well.

Already, we are capable of offering as good an education as any

established departments. Sociology, I might add is doing particularly

well within academic limits as well as with regard to extra-curricular

activities. Personally, my interest was not to simply set up a little

training shop, but to establish an institute that was worth its salt.

Overall, this will take considerable time and effort. But already I can

see the results of our efforts. It is good when one’s colleagues also

share a common dream and are showing considerable enthusiasm. In Sri

Lanka I was getting tired of having to work with people who could not

see the difference between a vision and a hallucination which also

frustrated many well meaning people within the university system, and

many of them succumbed to that sense of intellectual lethargy.

Ranjit Perera: Is that why you resigned? Many people in the university system and not just in Colombo were very surprised at your resignation.

Sasanka Perera: No that was not why I resigned. I did not

have any intention of resigning or leaving the country for too long when

I applied for this position at South Asian University. My intention was

solely to help set up a university for which tax payers of our country

and seven other SAARC countries are contributing heavily, and return in

five years or less once that institution had achieved some stability. On

one hand, I was following a personal dream in trying to set up an

institution that I thought would be a centre for academic excellence. On

the other hand, I enjoy teaching. It is under a similar situation I

resigned from the World Bank and came back to the Colombo University

about 10 years ago when I was offered a permanent job in the World Bank.

Ranjit Perera: So at that time, you came from the affluence of the World Bank to the poverty of the University of Colombo.

Sasanka Perera: Yes. As many people said at the time, it was

financial suicide. But Ideologically, I still think I made the right

decision. But the poverty I faced at the University of Colombo was not

only financial. It was also intellectual. But this is an unenviable

situation one can see in all of our universities, and not just in

Colombo. I never regret my decisions; it would simply a waste of time.

Hopefully, some students benefited from my decision. But as recent

events have clearly shown, obviously the university itself did not

appreciate it nor had any need for my services. But then, who am I to

question the collective wisdom of its entire governing board, which

thought that I should not be given five years no-pay leave to set up a

regional university which our country was partly paying for, but instead

thought my resignation was more preferable.

Ranjit Perera: After nearly 20 years of service to the

university and the country, the attitude of the University of Colombo

must have made you very angry and bitter? I know you have quite a

temper!

Sasanka Perera: I take these things in a stride. The temper

you talk about comes and goes. But like a dangerous animal who must be

caged, I have caged it quite well. It still comes out once in a way. But

I throw it back in. So in this instance anger had no resonance in the

feelings I had. I kind of expected the university’s attitude as I had

watched quite sadly its intellectual caliber diminishing and mediocrity

being entrenched in recent times. I may have been saddened, but not

angered. As I said before, who am I to question the collective decision

of such an august body like the governing board?

Ranjit Perera: But isn’t that denial illegal?

Sasanka Perera: No it is not. I was already on sabbatical

leave, and it was to run out in June or July 2013. What I asked for was

no-pay leave for a period of just over four years so that I could

complete the work in New Delhi that I was planning to begin in late

October. I made my application in July 2011. Up to today, this is August

2012, I never got a response to my request from the Colombo University.

Perhaps the Vice Chancellor was very busy. But I know, legally the

university does not have to give that kind of leave ordinarily. But this

is not an ordinary request or an ordinary situation. This was a

prestigious appointment and recognition conferred upon a scholar from

the University of Colombo. In any civilized part of the world, any

university would have perceived this as an honor that should be

celebrated. In such climates, if the necessary legal frameworks or

regulations did not exist, I think they would have done their best to

find means to accommodate something like this. The bottom line is that I

did not even get a response to my letter at least rejecting the request

for leave. Our universities are very quick to offer unconditional leave

that is annually extended if this was a political appointment. Here,

this was an academic appointment of significant propositions. But

unfortunately, no interest was shown in this matter whatsoever. So I had

no option but to resign.

Ranjit Perera: So is Sri Lanka well represented in the South Asian University’s academic staff?

Sasanka Perera: No. I am the only professor and senior

academic administrator. Sri Lanka cannot and will not be well

represented if scholars with an interest to come to South Asian

University from any Sri Lankan university have to undergo what I had to

endure. Unfortunately, it also created a very bad impression of Colombo

University in particular and Sri Lankan university system in general in

the minds of the many people who got to know about the incident.

Compared to this very Sri Lankan attitude, I was very touched by the

extent to which people in Delhi went to accommodate me even though they

did not know me personally at all. They went that far only because of my

qualifications and experience. Nothing else. I think this is something

the university system and the Higher Education Ministry should look

into. What this effectively means is that despite the enormous amount of

money Sri Lanka annually spends on the South Asian University, country’

scholars will not be able to serve it unless they resign. If this

happens, then the country will lose individuals which it can ill afford

when the government is quite flippantly talking about creating a

knowledge hub. Perhaps our politicians can create instead a gossip hub

where mediocrity will reign supreme. Compared to this situation,

individuals from all other countries have been given leave by their

parental universities or other organizations on very flexible terms to

come and serve the South Asian University and return if they wish. So it

is not an accident that Sri Lanka is underrepresented among the

academics of the South Asian University. And it will remain so.

Ranjit Perera: Well, even though you may not be appreciated

by the powers that be, you are at the forefront of establishing a

regional university of significant proportions. From that

institution-building and intellectual perspective, what is your take on

the status of Sri Lankan universities at present and the ongoing strike

by FUTA?

Sasanka Perera: I have written about this many times focused

on higher education in social sciences and humanities generally and

about the status of my own discipline in particular. In general,

universities started going into a decline since about the 1970s, and

this is much more visible in the social sciences and humanities. It is

also clear in medical education I think where an over-emphasis on the

technical aspects of medicine has shorn the training given of the

philosophical aspects of that profession. This whole issue is a separate

discussion and I doubt of we have the time for it today. But by now,

and particularly under the ruling oligarchy, higher education has seen

incredible reversals in recent times. Today, amongst our vice

chancellors, in my assessment there are only handful of people, if at

all, who have the intellectual caliber to hold such positions. This is

not a matter of having a PhD. That I hope everyone has. This is about

having the intellectual sensibility, integrity and leadership qualities

to be true leaders and innovators in the local academia. Instead of

scholars with wisdom, we have petty politicians who owe their

appointments and survival to the party in power. So their interest is

not academic but narrowly and crudely political and self-serving. You

can see this in the so called ‘voice cuts’ that many such people offered

on behalf of the incumbent president and Sarath Foneska at the last

general election. Meddling in party politics and peddling influence in

local politics should not be the vocation of any academic yet alone vice

chancellors. They can naturally vote for whoever they want, but they

have no business getting into such predictably compromised positions

while they hold office. Unfortunately today, most people interested in

high positions within universities are not necessarily the best and the

brightest. Given the entrenched pettiness in these institutes, many such

people are those who are willing to compromise and who have no sense of

self worth. Of course there are exceptions, but this is generally no

longer the rule.

Ranjit Perera: So you consider FUTA’s struggle a just one

even though the regime says it is playing with the future of the younger

generation. And academics deserve a pay hike?

Sasanka Perera: Well, you need to take different things in

their specific contexts. Personally, like many other citizens I know, I

have no doubt it is a just agitation. I also think, it is an overdue

agitation. As you know quite well, academics in our country have hardly

resorted to serious and sustained industrial action, and this is

certainly the case over the last two decades or so. Asking for six

percent of the GDP be set aside for education and requesting that they

be consulted in decision-making that has to do with the education sector

are not only reasonable but necessary. The issue is that it has taken

this much time for academics to get their act together to make this and

other related demands. As for the salary increase, I think most people

in Sri Lanka except politicians need a salary increase. If it does not

come as a process of regular policy-making, then it must be acquired.

This is what is going on now. If anyone is playing with the future of

the younger generation, it is the ruling oligarchy for its singular

inability and lack of interest and vision to deal with the prevailing

situation.

Ranjit Perera: One could always say you are over sympathetic

to your former colleagues and that you do not see their faults? After

all, you have been involved in the academic trade union system for quite

some time.

Sasanka Perera: Unenlightened people can say what they want

as they have many times before, and as they will many times in the

future. It makes no difference to me. When I joined the University of

Colombo in the early 1990s, I became the secretary of the University of

Colombo Teachers’ Association. At that time, the president was Chanadana

Jayaratne from the Faculty of Science. When the Arts Faculty Teachers

Association Colombo University was initiated a few years ago, I was the

founder president; most of my time was taken up trying to get a

constitution formulated. Compared to the activism of teachers at

present, my involvement was marginal. But none of this means that I am

incapable of seeing the failures and fault lines of the system. As I

mentioned a little while ago, a dangerous mediocratization and

politicization of universities have been going on for quite some time.

It would be naïve to assume that the negative processes in the wider

society would not be reflected in universities. Whatever is wrong in our

society is also visible in the universities. So given this situation,

there are many individuals who should never have been in universities.

But they are there due to the failures in the system. But right now, as a

trade union collective, it is not within FUTA’s mandate or that of any

other university trade union to look into this matter. It is beyond

help. What can be done is to ensure that at least in the future more

stringent entry requirements are imposed for university recruitments.

But to encourage good people to come into the system, they have to be

attracted with a decent salary and better working conditions which means

academic freedom among other things. That is one of the demands of FUTA

which I fully support.

Ranjit Perera: Then you would support any program that is

put in place to attract competent scholars from other countries to Sri

Lankan universities?

Sasanka Perera: Naturally, I would. I have heard that there

is some interest at UGC to lure back some of our own people who left the

island for greener pastures. I do not know the authenticity of this

story. But if the government’s demonstrated attitude and marked

hostility towards FUTA’s demands as well as the public vilification of

its leaders and blatant threats against them are an indication, I guess

this is a mere story with no substance. I doubt if the university system

or the government and its agencies are capable of attracting anyone of

significant caliber from oversees to our universities when they cannot

even keep the ones who are already here in place. My own recent

experience demonstrates this quite well. The slogan of creating a

knowledge hub that the government is repeating like a manthra

amounts to nothing other than a series of words that does not make

sense. To do this kind of thing, not only the universities but

associated services as well as the nature of the public sphere itself

and forums of cultural and intellectual production have to radically

transform. I don’t see this happening, and I also do not see anyone in

the oligarchy or the bureaucracy with the imagination to even think of

such things. Some academics on the other hand can help do this, even

though their voices are constantly stifled.

Ranjit Perera: Let’s get back to the South Asian University.

I have heard from some people in the diplomatic circle that the

decision to establish the university in New Delhi came about as a result

of arm-twisting by Indians and that it would have been better if it was

established in a more neutral place like Kathmandu or Colombo. What is

your take on that?

Sasanka Perera: Well, I am not privy to all the diplomatic

intrigue and discussions that might have preceded the establishment of

the university. But there was a clear agreement that New Delhi should be

the location for the university though there are provisions for

regional campuses in other cities in the region. Where else other than

Delhi would you be able to set up something like this? In cultural and

intellectual terms and in terms of the availability of facilities such

as libraries, Delhi clearly is the best place. Naturally, Colombo is a

more functional city where everything works relatively well; but

intellectually and culturally it is dead, and on top of that we are

encumbered with a regime that has not shown any vision when it comes to

higher education. In my mind, that disqualifies Colombo. If Sri Lanka

was given the option, the university might have ended up in Hambantota

and might have been named after the president.

Ranjit Perera: So in your own mind, this is the right thing to do?

Sasanka Perera: Absolutely. It is a brilliant idea. But it

is not a fairy tale. There are a lot of problems. These are not

intellectual problems but procedural ones. For instance, as a foreigner,

despite my five year special visa, I had a tough time opening a bank

account and it is quite difficult to send money home in an emergency.

Getting a gas cylinder for cooking was quite an operation. Visa itself

was a painfully slow process at the Indian embassy in Colombo. Even when

I finally got it, an endorsement was placed on my visa and that of my

wife’s saying that we had to register with the police each year. This is

despite an act of Parliament passed by the Indian Legislature trying to

make this a smooth process. Finding accommodation was very tough and

the university itself offered no help in this regard. These kinds of

situations would clearly discourage foreign academics coming to the

university. Naturally a lot of things need to improve. But then, it has

only been in operation for about two years.

Ranjit Perera: Is there anything else you would like to say before we conclude? It has been good talking to you after quite some time.

Sasanka Perera: Not really. I have already talked too much.

But I don’t believe that in our region and in our country or for that

matter, anywhere else in the world, regimes should be allowed to shape

our realities, dreams and the future beyond a point. This is

particularly so when it comes to situations where regimes have failed

their moral authority to govern. Citizens have to take decisions that

would shape their own destinies or at least they must try.