By Namini Wijedasa

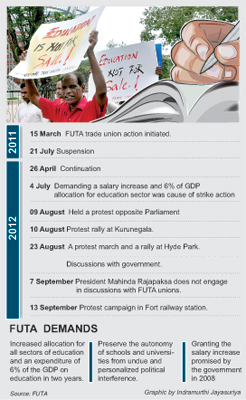

http://www.lakbimanews.lk The government has cancelled plans to use forced arbitration – an internationally criticized practice – to settle the two-month-old strike by university lecturers.

Economic Affairs Minister Basil Rajapaksa, who held another round of talks with the Federation of University Teachers’ Associations (FUTA) on Friday night,

confirmed that the Labour Department has been instructed to stop the proceedings.

FUTA was called to the Ministry of Labour on September 10 and handed a letter stating that its ‘industrial dispute’ with the University Grants Commission (UGC) will be settled through arbitration. The union was asked to nominate an arbitrator on its behalf.

The academics maintained, however, that their action could not be termed an ‘industrial dispute’ between FUTA and the UGC. “The issues raised by FUTA are policy related and need to be addressed through good faith discussions,” a statement said. “We have sought legal opinion on this issue and we have been advised that we need not comply with the request to seek arbitration.”

The website fairarbitration.com explains that, in forced arbitration, a company requires a consumer or employer to agree to submit any dispute to arbitration. “The individual is required to waive their right to sue, to participate in a class action lawsuit, or to appeal,” it states.

Jailbird ministerHigher Education Minister S.B. Dissanayake – whose relations with academics continue to deteriorate – supported the use of arbitration in the dispute. In a recent interview with LAKBIMAnEWS he said that if FUTA does not return to work, “then we will be forced to seek the intervention of the labour commissioner to resolve this matter once and for all.”

FUTA reacted against Dissanayake with a stinging statement that said, among other things: “The uncouthness of the minister has no bounds, which had previously landed him even in jail. Placing a jailbird as a minister of Higher Education and the meagre funding allocations (to education) in itself shows the attitude of the government to education in the country.”

Friday’s meeting with Rajapaksa lasted around two hours, ending past 10.30pm. Nirmal Ranjith Devasiri, FUTA convenor, said he felt positive about the meeting. The minister also revealed that the two sides are edging closer to a resolution. He said he hoped the strike would be called off this week, once several scheduled meetings are completed.

But Mahim Mendis, FUTA spokesman, said yesterday that, “We shall not end this struggle until there is clear agreement. The two mammoth processions are planned for the 24th (September) with joint trade unions and students.” There is also to be a public rally with students and trade unions on September 20 in Getambe, Kandy.

Meeting positiveMeanwhile, FUTA has also set up a special fund for its members who have not been paid since the strike started on July 4. In a letter currently in circulation, the union states that its members are facing financial difficulties. FUTA is seeking donations or to sell t-shirts at Rs800 each. The fund, which was launched last week, is yet to attract any high-profile contributors.

“It is highly likely that we will not be paid this month either,” the letter says. “This money will also go towards legal costs for FUTA with regard to certain cases that have to be filed on behalf of members who have been victimized due to their participation in trade union action.”

Minister Rajapaksa was hopeful that the dispute would be settled on “Monday or Tuesday.” “The main thing is that after we decide on something, they will have to call off their action,” he stressed. “They can’t have protests. We have been very specific now on what we can do and what we cannot do.”

The minister revealed that minutes of FUTA’s last meeting with P.B. Jayasundere – at which the treasury secretary had made several verbal commitments – are now being drafted. These will be handed over to the union.

At Friday’s discussion, FUTA requested Rajapaksa to convene a meeting with vice chancellors of all universities. This is likely to take place tomorrow, the minister said. He also said the government would release to FUTA its “action plan” on salaries.

Meanwhile, Devasiri told LAKBIMAnEWS that the meeting with Rajapaksa was “quite positive.” He said FUTA representatives had steeled themselves for a discussion on forced arbitration. “We actually prepared ourselves,” he elaborated. “Our membership had the strong view that we must not give into that pressure. But in the end the government realized it’s not going to work for them and backtracked. We heard that SB is not in the same mood, but that’s ok!”

Devasiri confirmed that there will be another meeting. “Basil has a different approach,” he reflected. “I don’t know if it’s tactical or not. It probably is. But we don’t care too much about it if we can come to an agreement.”

Asked what was offered last week, Devasiri said: “It was what we had (already) discussed. We had an understanding the week before, that there should be an agreement with the treasury secretary to address the salary issue. There are also some other issues, specially related to university autonomy.” But he refused to disclose more, saying it is too premature to release details.

“Everything depends on whether or not this process is going to continue,” he asserted. “What happens often is that there is a positive process of discussion, then some other parties intervene – like SB or UGC, talking about arbitration, and everything takes a different shape. If the same thing happens again, it’s going to be a disaster.”

Mass campaign goes onAsked specifically whether FUTA will call off its strike next week, he replied: “It’s too early to say that but we will try our best to make use of the opportunity that opened up yesterday (Friday).”

Devasiri confirmed that FUTA’s mass campaign will continue under the broader slogan of ‘Save State Education.’ Students have also been invited to participate in its public rallies – something which FUTA had avoided in the past.

Asked why its policy had changed, Devasiri said there were two schools of thought within FUTA regarding the involvement of students. “One concern among a section of members is that getting students to come will project a negative image about FUTA, that we are using students to our advantage,” he explained.

Devasiri also confessed that all members were “not very happy about the kind of approach the students follow in terms of their methods of demonstration and agitation.” “At the same time,” he continued, “there is another view that the students are the main stakeholders. We cannot just ignore them.”

Asked whether FUTA will take responsibility for students missing their exam deadlines and their graduation dates, Devasiri said academics will discuss how to make up for lost time. “It’s not easy but we could probably shorten the term a little bit,” he said. “We have to find a solution.”

He said faculty board meetings will be held as soon as the strike is over. “We will devise a plan,” he added.

confirmed that the Labour Department has been instructed to stop the proceedings.

confirmed that the Labour Department has been instructed to stop the proceedings.